‘Witches used their brooms to fly off to midnight meetings, not to sweep the patriarchal floor’ (Dickerson, 1996: 119)

The Angel in the House refers to an ideal first suggested by Coventry Patmore in his ‘self-sacrificing heroine’ (Showalter, 1972: 207) who he believed to be the perfect woman. This ideology reflected the Victorian belief that women were predisposed to the domestic sphere of looking after the home and children, whilst men, in comparison, where made for the public sphere, which involved working outside the home and earning money. This stereotype of the Victorian woman is present in the subconscious of many writers of the period, particularly the female writers who are writing female characters. However, several critics state that Victorian writers did not always present a one-sided female, and a more varied and androgynous female exists most strongly in works of fantasy, or texts that include fantastical elements. Fantasy writers have written female characters who were both good and bad, demonic and angelic, motherly and strong. Magical women can combine the qualities of ‘two of the most harmful feminine stereotypes – witch and Madonna.’ They have the potential to harmonise two opposite qualities within the female psyche by being multi-faceted. ‘This uniquely positive combination shatters the Victorian myth of the helpless female Victorian Fantasy constituted.’ (Honig, 1988: 131)

I am interested in analysing the representation of these magical, witch-like women in novels by Elizabeth Gaskell and Charlotte Brontë, and then comparing this to the treatment of the same characters in works by George MacDonald. Will the character of the ‘witch’ give the female writers more freedom in which to rebel against the Angel in the House? Or will, like in most of Victorian life, the male author succeed in portraying a more rounded, androgynous magical female, without the boundaries of gender to hinder him?

Virginia Woolf said that ‘killing the Angel in the House was part of the occupation of a woman writer.’ (1931) Sandra Gilbert also corresponds with this idea by explaining that female writers of the nineteenth century tended to transform themselves into acolytes of magical women through their occupation. (2013) However, Elizabeth Gaskell was a novelist who seemed to remain safely within the accepted female sphere throughout her whole career, unlike the singular Brontë sisters or the ‘hysterical’ Emily Dickinson. Gaskell’s novel, Lois the Witch, offers a subversive perspective on witches and women, although at first instance it might read from a purely patriarchal and Christian viewpoint. Somehow, Elizabeth Gaskell was able to write on varied female matters without losing her position in society as the perfect Victorian woman.

Lois the Witch begins by describing the figure of the witch in purely religious terms: ‘The sin of witchcraft’ (65); ‘Is anyone possessing an evil power over me, by the help of Satan?’ (66) Here she combines a biblical rhetoric with the voice of a moral narrator, and therefore sets the witch against contemporary female conformity. She emphasises the nineteenth century classification of the female sphere by reiterating male-ordered, conservative margins through her own words. By the mere suggestion that Satan can influence and control a female, it is suggested that women are weak of mind, and prone to hysteria and madness. The statement that their imagination can be corrupted through ‘a little nervous affliction’ also parallels her definition of the witch with the common re-evaluation of the time: witchcraft was merely a fiction created by women in the form of ‘Witch-hysteria’ and hysterical and soft-minded women were prone to imagining they were possessed by the devil or a witch, when in fact, they were just mad. (McKay, 1841) Witchcraft resurfaced during the nineteenth century, as Basham notes, mere ‘mesmerism’ (1992: 101) which was linked intrinsically to ‘witchcraft and demoniacal possession.’ (Auerbach, 1982: 74) This idea is furthered within the text through the description of the witch as ‘forsaken’, signifying a feebleness to the female mind that gives itself to Satan. Gaskell’s description of witchcraft so far very much signifies the power of the psychological theory prevalent to the time. She also actively demarcates paganism as evil and sinful, and therefore expresses deliberateness in presenting the witch through purely patriarchal, religious terms. Gaskell’s writing is highly conformist, seemingly only to show the witch as a sufferer of a mental disease from which male science offers a cure. Like Elaine Showalter states, Gaskell seems to begin her novel ‘searching for covert, risk-free ways to present [her] feelings.’ (1972) Witchcraft and madness become a mask that the author can slip on when her reader is about to be shocked by the text.

Throughout the novel, Lois continuously is depicted as an outlander – she is always alone and removed from the wider, inclusive society from the very moment she steps off the boat in Boston. When she first approaches the settlement, even the trees are described as unusual, with different colour leaves than the ones back home; she is consistently presented on the margins of the text, always on the outskirts and unable to find a way in. Lois becomes an unknowable Other who remains separate throughout the story, even before she is accused of witchcraft. We never learn her backstory. We know very little of her considering she is the ‘protagonist’ of the novel. Gaskell, perhaps wittingly, presents her marginally and at odds to both herself and the story. Virginia Woolf wrote: ‘Never let anybody guess that you have a mind of your own.’ (1942: 83) and perhaps this is what the author is attempting to do. By setting the ‘witch’ against her own public moral compass, she is ensuring that she, as an author, remains safely contained within the Angel of the House sphere.

Lois’ position as an outlander is also the reason that she ends up being so easily labelled as a witch. No other character defends her, and even those she considered friends do not challenge the accusation. The other significant ‘Other’ in the story is Nattee, the family’s Native American slave, and she too, is tried as a witch without rebuttal. She is marginalised throughout the story due to her accent, her inability to speak English, her beliefs and her colour. In representing this similarity between the two witches, and uniting them in their fear, Gaskell creates an unexpected relationship between the two women and begins to edge out from behind the safe curtain of the patriarchal narrative that she had previously used.

This understanding of ‘sisterhood’ within the novel is far more radical than just a strong female friendship. It is not just connecting two women, but two of the ‘accused’, two witches; an educated, white Christian, and an illiterate, dark-skinned slave. Every barrier of Victorian society seeks to separate them, and yet they are unified within the text as oppressed women and, importantly, as witches. ‘And in comforting her, Lois was comforted; in strengthening her, Lois was strengthened.’ (119) There is a stability in the sentence that suggests the women are entirely equal. The supposed ‘savage’ (118) offers just as much comfort as the Angel. Witchcraft is seen to overturn all boundaries: racial, class, gender and imperial.

However, this is not the first time that Gaskell has been seen to seek to free the oppressed within her writing. As Prickett states in Victorian Fantasy, ‘Mrs Gaskell caused scandal among her readers by dealing with illegitimacy in Ruth, and even condoning a ‘fallen woman’’ (2005: 40) Clearly, although attempting to hide behind the veil of patriarchal narratives, Gaskell has a fondness for writing women as she wishes them to be, and writing acts such as this does push her out of this sphere of acceptability. On the path to gain ‘artistic autonomy’ (Showalter, 1972: 207), she is threatening her role in society as the perfect woman. Regardless, she continues to write in a very restricted narrative voice. Almost in opposition to this once more, the two witches spend the night tending one another’s ‘bodily woes’ (118) and waking with their bodies entwined and their faces in one another’s laps, suggesting lesbian overtones and the sexuality that is often mentioned in relation to female hysteria and witches. This surprisingly erotic language, however, is suddenly traditionalised again, as chaos seems to enter the text. Suddenly, Lois feels as though ‘her senses were leaving her, and she could not remember the right words.’ (114) A sense of mania seems to take over Lois, who, until this act with Nattee, had embodied all the acceptable feminine traits. This sudden deliberate insanity that overcomes Lois once she is accused of witchcraft echoes the Victorian rhetoric on female sexuality and the weak-minded woman who does not desire, and who is capable of hysterical, unlikely imaginings. This turnaround back to patriarchal narratives is accentuated with the narrative descriptions of Nattee. She is a ‘savage’ from the wild, unrestrained forests of Native America. (119) Her injustice as a slave parallels her injustice experienced as a witch perfectly, and ‘if there’s an ancestral curse, surely, it’s one that afflicts all colonists. Persuading themselves they are fulfilling the will of God whilst they have brought the original inhabitants into a state of slavery.’ (Packlow, 2000: 9) This is an accurate explanation of how the society views witches within the novel. The similarities between the witch and the slave are strikingly obvious, and this makes the new sisterhood between the two women very difficult to understand within the boundaries of the text. It is hard to distinguish a connection between what happens between them, and the narrative describing it. Nattee is described as ‘dirty’, ‘filthy’, a ‘poor savage’, ‘all astray in her wits’, with an ‘old brown wrinkled face,’ who must be cared for by the white middle-class English woman. (118) The old woman’s ‘dread of death’ also suggests the uncertain fate of the unreligious savages who do not believe in God, and the ‘poor scattered sense of the savage creature’ embodies similar suggestions of immorality, sin and madness, all of which are synonymous with the figure of the witch in Victorian literature. In Gaskell’s exploration of the witch, she begins to single out the ‘troubled area of women’s communion.’ (Dickerson, 1996: 122)

Gaskell’s writing continues to exude a desire to enforce Christian dogmas. Towards the end of the story there are yet more references to the ‘external comfort’ of the ‘Heavenly Friend’ and the ‘one who died on the cross.’ (119) However, in the moment of her death, Lois does not call out to Jesus, or God, but to ‘Mother!’ (120) This dramatic and unexpected declaration of a capitalised Mother suggests an overtly female faith that, in all ways, pushes against the male boundaries of Christianity and undoes all conventional mentions to religion within the text. By enabling Lois to call for her own God, who in inherently female, Gaskell refuses patriarchy with finality in a stunning declaration of matriarchy.

This parallel between witches, women and Christ continue as Lois and Nattee’s hangings are described in the same vein of ‘the one who died on the cross for us and for our sakes.’ (119) Re-writing the apparently hysterical woman as a Christ figure is extremely subversive and causes us to question all the patriarchal narrative devices that led up to this point in the book. Did Gaskell intend for the reader to believe in the moral narrator and her patriarchal viewpoint, just to increase the shock of controversially defying it? Or was she deliberately conscious of the boundaries of her own place in the world, and the tentativeness of her position as the perfect woman in her own life and society? Christ was victimised, beaten and suffered as a martyr for the ‘greater good’, and these are all qualities that offer themselves as important symbols for the social and political suffering of women, particularly in the Victorian era. Simone de Beauvoir articulated women’s connection to Christ: ‘As women bleed each month and in childbirth, so Christ bled on the cross; as women perceive themselves as sacrificial victims of men, impaled in the sexual act, so Christ was pierced by the spear. She it is who is hanging on the Tree, promised the splendour of the Resurrection. It is she: she proves it: for her forehead bleeds under the crown of thorns.’ (1969: 117) Indeed, when Lois is finally granted death, she is the happiest she has been in the entire novel, finally faced with the sanctity of ‘Mother!’ and freed from the pain and humility of suffering as a woman and a witch.

Like Gaskell, Charlotte Brontë was a female novelist who used the ‘supernatural to explore and express differences and oppression.’ (Dickerson, 1996: 104) Brontë’s use of supernaturalism, witches and ghosts constituted a space to open and explore the realities and oppressions of women. ‘Like Shakespeare’s three witches, the Brontë girls are associated with storm and violence, lightening flashes, heath and moorland.’ (Grosvenor Myer, 1987: 11) Charlotte and her sisters, just like their texts, have always escaped the patriarchal, sensible boundaries of explanation. Many critics have found their novels hard to pin-down to a genre – some have said they are Realist, Gothic, some Fantastical, Romance. Like Sandra Gilbert’s earlier definition, and very much unlike Gaskell, they take on a supernatural, mystic persona themselves that influences their writing and other’s readings of their work. The symbolism of witches and supernaturalism is abundant in their texts: Cathy Earnshaw is called a ‘ghostly female witch-child’ in Wuthering Heights, Rochester accuses Jane Eyre of ‘bewitching’ his horse, and even Mrs Reed could be depicted as a figure emanating strong witch-like symbolism, albeit in the form of the Evil Stepmother.

In Jane Eyre, Brontë often describes Jane in spectral and unnatural terms through the eyes of the male characters. ‘The accusation of witch springs from an intense societal fear of a powerful, untrammelled woman who defies social norms.’ (Pratt, 1981: 122) and it is through their misunderstanding of Jane that the males in the story misjudge her and almost ridicule her for her mystical powers. She is described as ‘a mere spectre’ (296), and when first encountering Rochester, he teasingly accuses her: ‘When you came on me in Hay Lane last night, I thought unaccountably of fairy tales, and had half a mind to demand whether you had bewitched my horse: I am not sure yet.’ (143) ‘So you were waiting for your people when you sat on that stile? … For the men in green: it was a proper moonlight evening for them. Did I break through one of your rings, that you spread that damned ice on the causeway?’ (144)

Unlike Gaskell, Brontë is not afraid to delve into the suspicions surrounding witchcraft and women. Like her author, Jane Eyre belongs to the supernatural realm, not to the rigid, Victorian, utilitarian world of Mrs Reed and Brontë’s own society. This is Brontë’s method of freeing an oppressed woman from the hold that society has over her. As a child Jane wails: ‘Why was I always suffering? Always brow-beaten? Always accused? For ever condemned?’ (12) She had been mistreated all her life, because there was yet no character who understood her. Until Rochester, no character was able to see past plain Jane, and into her spirit. It is only when she sees her own power, her own self, when she investigates the mirror and notices the ghost of herself ‘specking the gloom’ (11) that she begins to build her own agency and grow into herself. Rochester says: ‘You are altogether a human being, Jane? You are certain of that?’ (385) He is the only other being who recognises her for who she is, altogether more supernatural than the natural or patriarchal world.

Like Lois, Jane often finds herself on the margins of the action. She is always between one place and the next, always on the outside, looking in. She feels torn between her love for Rochester and her duty to St John, and never truly fits in at either Gateshead Hall, Lowood School or Moor House. She constantly runs the risk of being halved: ‘Alas! If I join St John, I abandon half myself.’ (356) She is the stranger, the ‘spectre’, the one who watches and ‘bewitches.’

However, strangely, whilst at Moor House, it is St John who is truly represented as the ‘witch.’ He mesmerises Jane: ‘I felt as if an awful charm was framing round and gathering over me’ and ‘I trembled to hear some fatal word spoken which would at once declare and rivet the spell.’ (353-54) ‘I felt his influence in my marrow, his hold on my limbs.’ (357) St John is also described as a ‘strange being’ (365) Suitably, whilst Jane is under his hold, her own powers and witch-like abilities are severely diminished. She feels as though she is mesmerised and bewitched by St John, to the detriment of herself. For, if she stays, she will abandon herself. Therefore, her true nature lies with Rochester, across the moors, and although St John tries to banish her wanderings towards him and wishes for her to touch the bible and the ‘sacred cross’, she will not.

Madame Walravens of Villette is a witch-like character within Brontë’s work who is represented differently from Jane Eyre. Her mysteriousness and demonic power are heavily implied throughout the novel and, unlike Jane, she is the hallmark of the typical nineteenth century witch. She has the typical appearance of an old, evil witch: she is a mere three-feet high, shapeless, with skinny, knobbly hands that hold a gold wand-like ivory staff. She often disappears just as mysteriously as she appears. When Madame Walravens turns to leave after cursing Madame Beck, a peal of thunder breaks out. Her house appears as an ‘enchanted castle’ and the storm is a ‘spell-wakened tempest.’ (346) This is synonymous with the Brontë’s depiction of witchcraft and the supernatural as a whole: the weather is important in creating a powerful, atmospheric suggestion of immortal power. Wuthering Heights also exudes a stormy, desolate narrative, with lots of foreshadowing and pathetic fallacy, and Jane Eyre herself travels far across the moors whilst the thunder and lightning rockets above and the rain lashes down, almost sending herself into a fit of hysteria.

Madame Walravens name is also highly suggestive. The raven is a traditional Celtic image of a hag (or witch) who destroys children, and Walravens herself destroyed a child by imprisoning her: Lucy is told that she caused the death of her grandchild, Justine Marie, by opposing her match with the poor and lowly Paul and causing her to move to a convent and die. ‘To have a raven’s knowledge’ is also an Irish proverb meaning to have a seer’s supernatural powers. Walravens witch-like imagery – the deformed body, staff, malignant look and old age is suggestive as to the inspiration of her character. You could even say that she is yet another madwoman in the attic, coming downstairs from the top of the house, malevolently enraged just as Bertha Mason is in Jane Eyre, ‘with all the violence of a temper which deformity made sometimes demonic’. (Gilbert, 2000: 431)

George MacDonald, innovator of fantasy and fairy-tales, is another Victorian author whose representation of witches is something that is included in almost all his texts. He presents his female characters in a way that deliberately causes us to ‘reconsider our attitudes to sex roles and sexual stereotyping.’ (McGillis, 1992: 10) Gillian Avery also notes that Victorian children would ‘understand’ and maybe even ‘expect’ that fantasy, like traditional fairy-tales, would provide ‘purpose and a moral code; good would be rewarded, evil punished.’ (2015: 128) In the fairy story, The Romance of Photogen and Nycteris, Watho, the witch, is the very antithesis of the ideal Victorian Angel in the House. Jack Zipes said that ‘MacDonald uses fantasy to experiment with conventions to undermine them and illuminate new directions for moral and social behaviour.’ (1983: 105) This could indeed be what MacDonald is attempting to do. In portraying Watho as the typical nineteenth century, evil witch, will he then subvert the stereotype? Watho is a witch who is desperate for knowledge, masculine and aggressive, and filled with desire, and holds similar traits of the ‘first witch’ Lilith, who is often envisioned as a dangerous demon, who is sexually wanton, and steals babies in the darkness. (Hammer, 2018) Watho captures and keeps Photogen and Nycteris from birth and attempts to undertake an experiment by drastically controlling the experience of their world. Her craving to control and ‘play God’ puts her in the same league as Dr Frankenstein and Faust, whose excessive need for knowledge turned them evil. (Honig, 1988: 115)

‘For those actually living at the time it was a period of intense anxiety and self-doubt’ (Prickett, 2005: 38) and the literature of the time often betrayed the fears of the society. The Victorian period was a time when scientific and social changes, particularly Darwin’s evolution theory, was causing hesitancy and fear in the mind of the middle-class. MacDonald’s characterisation of Watho reflects the widespread apprehension and uncertainty around the moral implications of frightening discoveries about man and creation. Watho is the perfect combination of the wicked stepmother and the deranged scientist, and this ambiguity of her gender and her ability to rebel against female conformity is highlighted by this blending of traditionally feminine and masculine traits. Her masculine desires cause her to breed two babies under experimental, immoral conditions. The Day Boy is never exposed to darkness, and the Night Girl is never exposed to daylight. By experimenting on young children without conscience, she perverts the first and most regarded feminine characteristic of nurture, and instead, revels in the scientific analysis of the masculine. This corruption of the ‘Angel in the House’ of true Victorian womanhood is presented as so unnatural, even in this fantasy story, that it is explained away by Watho’s ‘wolf’. The mention of the wolf recalls a parallel with Gaskell’s treatment of the magical woman – in order to explain the multidimensional parts of femininity, an external influence must be to blame. In Lois the Witch, it is Satan who drives the demonic witch to possess the woman. In MacDonald, it is the wolf, a creature who is dangerous, instinctual, and without morals. ‘She was not naturally cruel – but the wolf had made her cruel.’ (304)

Whilst the nineteenth century widely regarded mothering as ‘the most important job imaginable’, along with this idealisation came the ‘implication that any intellectual or spiritual failing in the child can and should be attributed to the mother.’ (McKnight, 1997: 4) In the Victorian era, the mother’s influence on her child was both appreciated and deeply feared, and McKnight states that this ideology taught that the mother ‘is the greatest creator that must be tamed… she is all-important… but she better not try to be too important.’ (18) Watho therefore attempts to be ‘too important’ in her moulding of the children. When the Night Boy, Photogen, becomes ill despite all her attention, Watho starts to feel extreme hatred towards him because he was ‘her failure.’ (331) ‘It is the peculiarity of witches, that what works in others to sympathy, works in them to repulsion.’ (330) She then delves even deeper into psychopathic mania by letting her passion build and build, until, no longer able to control herself, she torments and pricks Photogen until he dies. (331) ‘Before long, Watho was plotting evil against her’, and she then ‘soothes her wolf pain’ (note: not her own pain) by exposing Nycteris to the burning sun and watching her die. (350) These dark and twisted desires and irrational emotions are attributed to the wolf inside her, and not the woman.

‘She is full of powers of destruction, of desolation, and of chaos, but at the same time is a helpful figure’ says Franz of fairy-tale’s double-woman figure, who is destructive and evil, and yet also a mother-figure. (Dundes, 1988: 215) This is a positive representation of a woman, and witch, in the sense that it avoids one-sided female identity and shows a multi-faceted person who is neither feminine nor masculine, but both. However, reflecting on the fact that MacDonald’s stories are meant for children, Bettelheim says that children would not find these more realistic combinations of difference appealing, since many young children are not comfortable with dealing with the possibility of both good and bad in their own mothers. Bettelheim sees the one-sided characters in MacDonald’s work more helpful because whilst ‘the fantasy of the evil stepmother thus preserves the image of the good mother, the fairy tale also helps the child not to be devastated by experiencing his mother as evil.’ (2010: 69) MacDonald, however, has famously said himself that ‘I write, not for children, but for the child-like, whether they be of five, or fifty, or seventy-five.’ (cited in Gray, 2011: 13) His stories have kept their appeal for all because the characters retain their overall place in the story. The witches are the antagonists, although we can read into the subversion of stereotypes in them, and children will see only the ‘evil’ witch, and will not read into the subtle, interwoven interpretations that adults will draw from analysing them. In the case of Watho, her actions are explained by MacDonald as ‘In the hearts of witches, love and hate lie close together, and often tumble over each other’ (331); a statement that is true of all human beings, hence making Watho seem a little less monstrous and a little more human. It is only when she turns into a wolf that she can finally be killed, and this perhaps suggests that she is so powerful in her androgynous female form that she is indestructible.

Auerbach, in analysing Old Irene of MacDonald’s stories The Princess and the Curdie and The Princess and the Goblin, states that her witch-like figure represents ‘the release of the victim into the full use of her power’ – as a victim of the Victorian feminine expectation. (1982: 39) This character of Old Irene, is an extremely positive figure in the text, and yet still owes much of her characterisation to the evil witch in Sleeping Beauty. When the Princess Irene encounters Old Irene for the second time, the sequence parallels Briar Rose’s encounter with the Bad Fairy almost exactly. Both girls are in a dreamlike state, and walk up a long, circular staircase almost against their will. Bettelheim, commenting on Sleeping Beauty, tells us that ‘such staircases typically stand for sexual experiences.’ (232) It is the first time that these girls will explore ‘the formerly inaccessible area of existence, as represented by the hidden chamber where the old woman is spinning.’ (233) Both girls enquire about the spinning because it symbolises the secrets of being a woman – Bettelheim states, not so much intercourse, but menstruation. This explains why no male figures are needed for this scene at all, and why Princess Irene’s finger is already wounded.

This is where the two tales differentiate – in Sleeping Beauty, Briar Rose pricks her finger and then falls into a long, protective sleep, which will ward off any sexual encounters until she is old enough, but in The Princess and the Goblin, Princess Irene spends the night with Old Irene, and undergoes further sexual initiation. Old Irene heals her wounded finger: ‘she rubbed the ointment gently all over the hot swollen hand. Her touch was so pleasant and cool, that it seemed to drive away the pain and the heat wherever it came.’ (121) The old witch then invites Princess Irene to sleep with her and even asks, with some degree of coyness: ‘You won’t be afraid to go to bed with such an old woman?’ (121) The princess says that she is not afraid, and so the old lady ‘draws her towards her’ and ‘kissed her on the forehead and the cheek and the mouth’ (122) When they are in bed together, the old lady undresses and asks: ‘Shall I take you in my arms?’ (123) In the morning, the Princess’s finger has healed and ‘the swelling had all gone down.’ (124)

This encounter is jarringly sexual and has some uncomfortable undertones to it. Although MacDonald is praised for his representation of women and androgynous femininity, it seems that he is unable to separate his own male perspective from this scene, as Princess Irene’s sexual initiation seems more masculine than feminine, with the swelling finger that requires ointment and has all gone down by the time morning comes. However, he is also inverting common fairy tale scenes in which the female bond is destroyed by male power. In Little Red Riding Hood, specifically Perrault’s version, Little Red Riding Hood is never warned about the wolf. (1697) She therefore ventures innocently into the wood and is killed by the wolf. In his story, the grandmother was powerless, the mother was powerless, and the daughter was powerless. It seems that, although it heeded a warning to girls about the danger of wolves, it was pointless in the sense that a woman would have been unable to save her daughter, or herself, anyway. In The Trials and Tribulations of Little Red Riding Hood, Jack Zipes also examines the historical story of the little girl. In Paul Delarue’s research, he finds a version of the story in which rape is explicit. (1993) Little Red Riding Hood escapes the wolf in this story, which obviously highlights her ability and resourcefulness, but which also emphasises the fact that she must face the wolf alone. Yet again, neither her mother or grandmother could help her; her mother fails to warn her, and her grandmother has already been eaten by the wolf.

MacDonald also inverts the bedroom scene from Little Red Riding Hood in The Princess and the Goblin, but without any such undercurrents. In this story, the little princess also visits her grandmother, but, for the Princess, there is no masculine interference of any kind. She finds her grandmother just as she had expected to. ‘The old lady having undressed herself lay down beside the princess’ (77) ‘Oh dear, this is so nice!’ said the princess. ‘I didn’t know anything it the world could be so comfortable. I should like to lie here forever.’ (77)

In conclusion, from my analysis of three different authors and their perspectives on Victorian fantasy, I am struck by the fact that, regardless of character or role in the story, all of the witches depicted seem to challenge and subvert patriarchal norms in some way. There is a clear difference between Gaskell’s treatment of the witch and her storytelling methods when compared with MacDonald’s more overt and obvious subversion of stereotypes. Gaskell wrote from a fragile position of Victorian femininity; she was not marginalised or pushed into a ‘fallen’ or ‘supernatural’ sphere in her real life, and therefore, was much more cautious in her narrative structure, and her treatment of witches. Brontë, in comparison, as part of a real coven of three witch-like sisters, relatively isolated and unmarried, seemed to have less reservations about gender boundaries and her role within society. Thus her depictions of witches and of women in general are powerful: ‘Brontë’s hunger, rebellion and rage are what led her to write Jane Eyre in the first place’ (Gilbert, 2000: 370) As an author, she was angry at the way that governesses, in particular, were treated in patriarchal society, and hence used that anger to create powerful female characters who transcended the boundaries of both the Angel in the House and the patriarchal religion of the time. Gaskell, although more conservative in her writing, takes the witch one step further with her exclamation of ‘Mother!’ Not only are witches, and women, not hindered by God and patriarchy, but their ‘God’ is a woman. MacDonald, writing translucently for children, although he claims otherwise, was also unafraid to be subversive. The witches in his stories, from Watho to Old Irene, all embody various traits that make them androgynous. They are not just motherly, but destructive too; they are angelic and demonic; sensitive and intelligent. Fantasy offers a medium through which to analyse the fears of the society of the time, and to create female characters that, on the surface, seem far removed and magical, but, are simply a representation of true women. The witch strategically represents both the historical abject figure subjected to death, and a radical fantasy of renewal in the form of a female figure who desires a cultural transformation. (Butler in Sempruch, 2008: 14)

Bibliography

Primary Reading

Brontë, Charlotte. Jane Eyre (London: Penguin Classics, 2006)

Brontë, Charlotte. Villette (London: Penguin Classics, 2004)

Gaskell, Elizabeth. Lois the Witch (London: Penguin, 2000)

MacDonald, George. The Complete Fairy Tales, (London: Penguin Classics, 1999)

MacDonald, George. The Princess and the Goblin, (London: Puffin Classics, 1996)

Secondary Reading

Auerbach, Nina. Woman and the Demon: The Life of a Victorian Myth (Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1982)

Basham, Diana. The Trial of Woman: Feminism and the Occult Sciences in Victorian Literature and Society (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1992)

Bettleheim, Bruno. The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales (New York: Vintage, 2010)

de Beauvoir, Simone. The Second Sex (London: Gallimard, 1969)

Dickerson, Vanessa D. Victorian Ghosts in the Noontide: Women Writers and the Supernatural, (Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 1996)

Dundes, Alan. Cinderella: A Casebook (Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988)

Gaskell, Elizabeth. Ruth (London: Penguin, 1997)

Gilbert, Sandra M. The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth Century Literary Imagination (Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2000)

Gilbert, Sandra M. I, Too, Will be “Uncle Sandra”, Dickinson Electronic Archives, 2013, online electronic recording: http://www.emilydickinson.org/titanic-operas/folio-one/sandra-gilbert [last accessed: 09/01/2019]

Gray, William. Fantasy, Art and Life: Essays on George MacDonald, Robert Louis Stevenson and Other Fantasy Writers (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011)

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm. ‘Hansel and Gretel’, Grimms’ Fairy Tales (London: Ernest Nister, 1986)

Grosvenor Myer, Valerie. Charlotte Bronte: Translucent Spirit (USA: Vision Publishing, 1987)

Guiley, Rosemary. The Encyclopedia of Witches, Witchcraft and Wicca (London: Infobase Publishing, 2008)

Haining, Peter. A Circle of Witches: An Anthology of Victorian Witchcraft Stories (USA: Taplinger Publishing Company, 1971)

Hammer, Jill. Lilith, Lady Flying in Darkness. https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/lilith-lady-flying-in-darkness/ [last accessed: 08/01/2019]

Honig, Edith Lazaros. Breaking the Angelic Image: Woman Power in Victorian Children’s Fantasy (London: Greenwood Press, 1988)

Hutton, Ronald, de Blecourt, William & La Fontaine, Jean. Witchcraft and Magic in Europe, Volume 6: The Twentieth Century (Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999)

Linton, Elizabeth Lynn. Witch Stories, (London: Chapman and Hall, 1861) scanned into Harvard College Library [last accessed: 08/01/2019]

McGillis, Roderick. For the Childlike: George MacDonald’s Fantasies for Children (Children’s Literature Association, 1992)

McKay, Charles. Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. (London: Harriman House, 1841)

McKnight, Natalie. Suffering Mothers in Mid-Victorian Novels (London: Macmillan, 1997)

Mendelsohn, Farah and James, Edward. The Cambridge Companion to Fantasy Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012)

Packlow, Jenny. ‘Introduction’, Elizabeth Gaskell, Lois the Witch (London: Penguin, 2000)

Pratt, Annis. Archetypal Patterns in Women’s Fiction (Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1981)

Prickett, Stephen. Victorian Fantasy (Texas: Baylor University Press, 2005)

Raeper, William. The Gold Thread: Essays on George MacDonald (Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2015)

Roper, Lyndal. Oedipus and the Devil: Witchcraft, Religion and Sexuality in Early Modern Europe (London: Routledge, 2003)

Sempruch, Justyna. Fantasies of Gender and the Witch in Feminist Theory and Literature. (Indiana: Purdue University Press, 2008)

Showalter, Elaine. “Killing the Angel in the House: The Autonomy of Women Writers.” The Antioch Review, vol. 50, no. 1/2, 1992, pp. 207–220. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4612511. [last accessed: 08/01/2019]

Showalter, Elaine. The Female Malady, (London: Virago, 1987)

Skey, F. C. Hysteria (London: Longmans, Green, Reader and Dyer, 1867)

Various. The Witching Hour – A Collection of Victorian Tales Concerning Witchcraft and Wizardry (London: Read Books Ltd, 2011)

Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One’s Own (London: Vintage Classics, 2018)

Woolf, Virginia. The Death of the Moth, and Other Essays (London: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1942)

Zipes, Jack. Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion (New York: Routledge, 1983)

Zipes, Jack. The Trials and Tribulations of Little Red Riding Hood (New York: Routledge, 1993)

Series: All Souls Trilogy

Series: All Souls Trilogy![]()

The year is 1945. Claire Randall, a former combat nurse, is just back from the war and reunited with her husband on a second honeymoon when she walks through a standing stone in one of the ancient circles that dot the British Isles. Suddenly she is a Sassenach—an “outlander”—in a Scotland torn by war and raiding border clans in the year of Our Lord… 1743.

The year is 1945. Claire Randall, a former combat nurse, is just back from the war and reunited with her husband on a second honeymoon when she walks through a standing stone in one of the ancient circles that dot the British Isles. Suddenly she is a Sassenach—an “outlander”—in a Scotland torn by war and raiding border clans in the year of Our Lord… 1743.

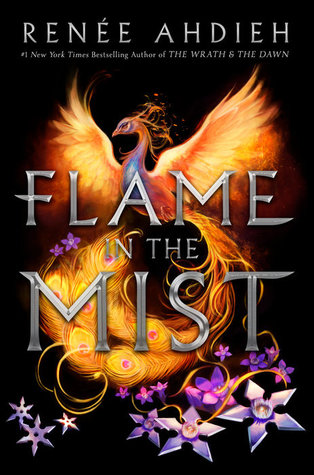

The only daughter of a prominent samurai, Mariko has always known she’d been raised for one purpose and one purpose only: to marry. Never mind her cunning, which rivals that of her twin brother, Kenshin, or her skills as an accomplished alchemist. Since Mariko was not born a boy, her fate was sealed the moment she drew her first breath.

The only daughter of a prominent samurai, Mariko has always known she’d been raised for one purpose and one purpose only: to marry. Never mind her cunning, which rivals that of her twin brother, Kenshin, or her skills as an accomplished alchemist. Since Mariko was not born a boy, her fate was sealed the moment she drew her first breath.

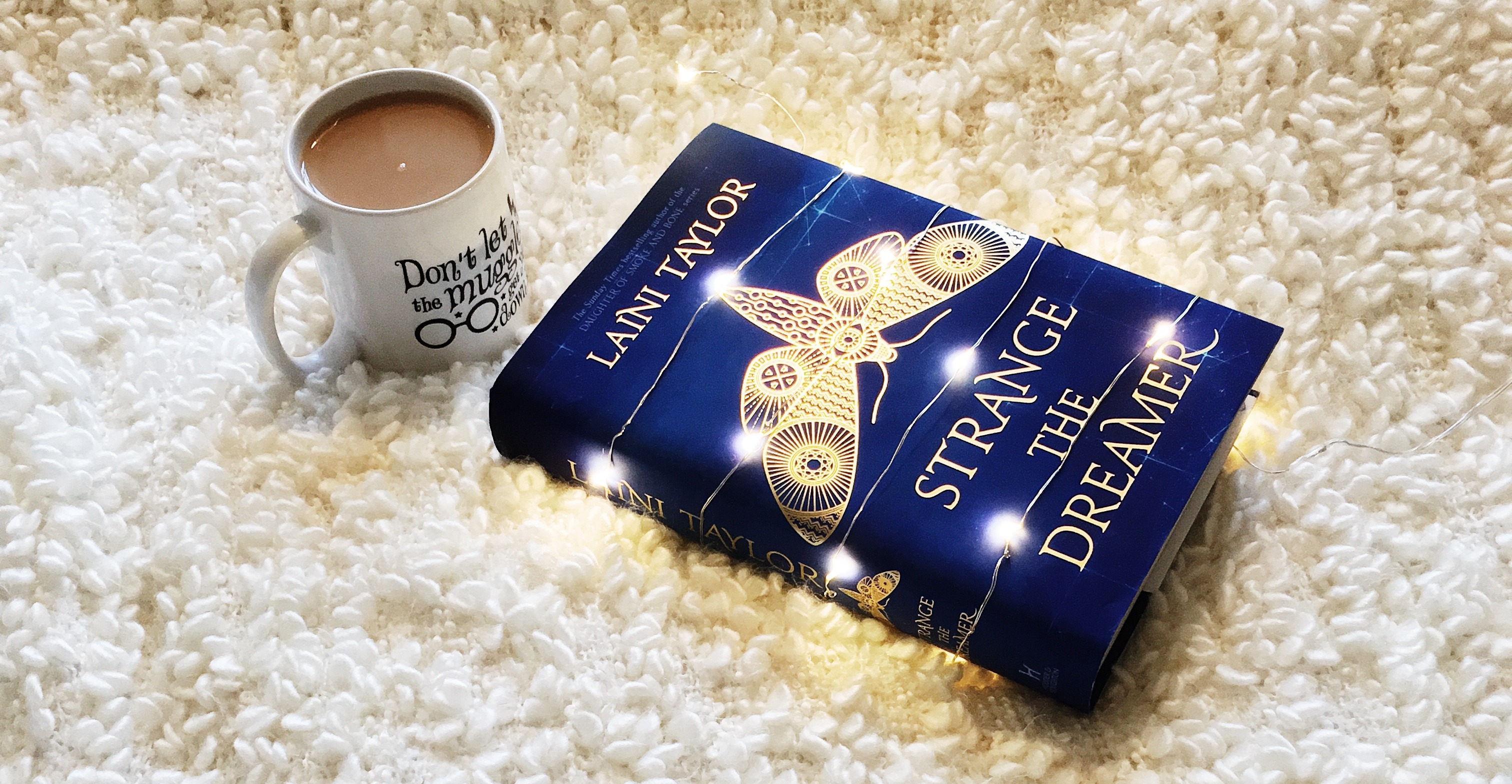

orphan and junior librarian, has always feared that his dream chose poorly. Since he was five years old he’s been obsessed with the mythic lost city of Weep, but it would take someone bolder than he to cross half the world in search of it. Then a stunning opportunity presents itself, in the person of a hero called the Godslayer and a band of legendary warriors, and he has to seize his chance to lose his dream forever.

orphan and junior librarian, has always feared that his dream chose poorly. Since he was five years old he’s been obsessed with the mythic lost city of Weep, but it would take someone bolder than he to cross half the world in search of it. Then a stunning opportunity presents itself, in the person of a hero called the Godslayer and a band of legendary warriors, and he has to seize his chance to lose his dream forever.